|

'More than …

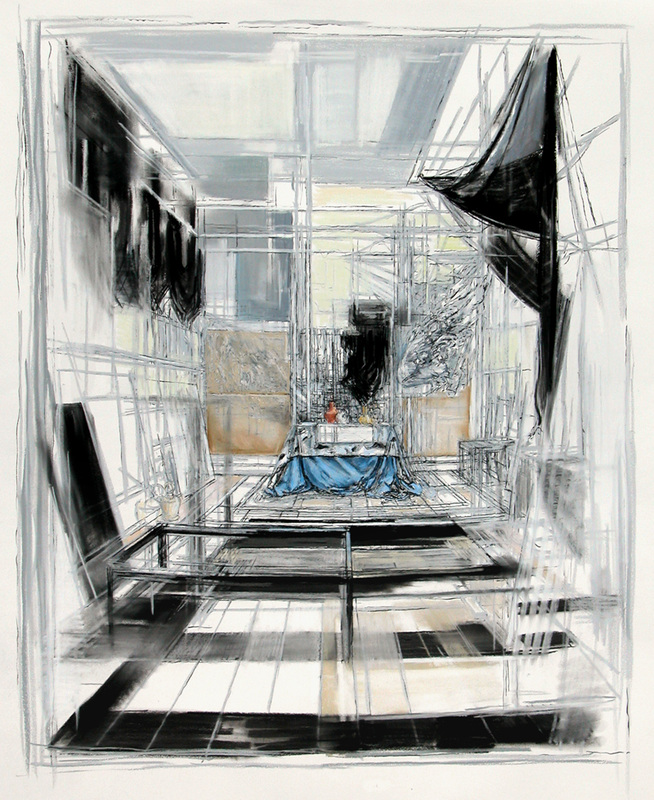

Still Life – the drawings of Nigel Buxton' by Cassandra Fusco Nigel Buxton is a Christchurch artist who trained at the Byam School of Art in London. Since moving to New Zealand he has developed a style that incorporates drawing and painting within the same work in order to evoke subtle constructions of space. His most recent exhibition at ‘Papergraphica’, Still Life, featured five works from an ongoing series. The image in the work of Nigel Buxton is never closed, nor is it a pre-planned narrative. Rather, each study is an embodiment of memory and time and, therefore, change. Such a statement might imply turmoil, the constant fray of modern exigencies. His most recent exhibition refutes any such surmise. Buxton’s still life works are studies of the modern mind moving through the contemporary landscape of perpetual change. But, with the quiet discretion of a draughtsman, these five drawings, spanning a period of over ten years, reveal not simply an assembly of pleasing objects in space but a mental ‘return-room’. In Georgian tenements, a return room was situated at the turn of flights of stairs and often functioned as a cloak room or small study. James Joyce wrote of one such room, flooded with light, a retreat from the surrounding darkness. In Buxton’s work we find a kindred space, one to which the mind may return, away from the exterior landscape of supersaturation and surface artificialities. In Buxton’s simple, almost bare, high-studded room, a table, set squarely against the furthermost wall, is draped with heavy fabrics and arranged with some glazed pots. These five large drawings on paper, worked in black ink and white chalk pastels with the occasional use of dull-rich ochres and Alizarin crimson, combine and quietly assert a reality of long use and the artist’s will and skill to draw simple vessels, arrayed almost altar-like. The simplified subject or common object is one of the features of the avant-garde of the early 20th century. But if we ask how such objects are used here, something more than the ‘still life’ study becomes apparent. Still life, like the study of the nude, has undergone several assaults. It has been accused of striving to build an art on the ordering of individual perception of objects and the human form when, in reality, the physics of quantum mechanics insists that life is unpredictable, unclosed and ever-changing. With the quietest imaginable lines, Buxton taps into this reality but draws objects as more than still life as celebrations of quiet domestic use pitched against an exterior world of perpetual motion. Simplicity here is not only a stylistic device, the reduction of form, but as an iconographic preference for the simple in the sense of ‘uncorrupted’ and unfinished (still full of use and possibilities). The vessels are, the artist says, handcrafted Spanish pots, some 30 years old. But their shape and function talks back to other times, other communities and, most importantly, they are clearly valued and used. On one level these works can be viewed as symbolic ‘histories’, not as explorations of decay a common connotation of still life studies, but rather, as a set of simple vessels on a table with an abstract ‘drip’ painting from the artist’s student days serving as both a back-drop and a reminder of the artist’s own development in time. On another level, the subtle changes of light and colour, and the artist’s inclusion of a painting in a very different style, alert viewers to the ‘space’ Buxton contemplates. It is, arguably, the axis of time – an alignment of past, present and future as experienced by the mark maker. The pictorial image (the room), with its minimal population, convinces us that the artist has been there, that he has seen and recorded it in three-dimensions. However, what moves these studies beyond this physical record is the additional sense of ‘when’ invested and available in each of the five works. This is conveyed through the unclosed quality of seeing and enquiry behind each drawing, a quality which, paradoxically, is made visible through its very translucence. In the exhibition notes, curator Marian Maguire writes that Buxton intermittently assembles these articles, almost ritualistically. “It is a kind of meditation,” she says, “in which he chooses to be in the room to create a visual honesty. … It is full of the time he has spent measuring the distance between himself and the props, his eye constantly networking across the void. … Buxton claims that everything is brought back to what is seen, but it must be the case that for him the room is full of past drawings, ghosts who haven’t quite left.” Even without this knowledge, the five works reveal subtle but deliberate changes, almost palimpsest. What gives them this sense of other times, of ‘when’ and difference, however, is not any change in the actual props, but rather, the quality of change laid down in the drawing itself. Lines define spaces and volumes then dissolve with a transparent quality that actually questions as much as it records apparent actualities. It is as though we too stand in the space but also outside it and beyond it. There is a sense of relativity in these works whereby everything is there yet nothing is tangible or concrete. There is an almost medieval sense of time in which past, present and future are seamlessly merged, creating a freedom within which we may move back and forth. So are these quasi-scientific experiments in seeing and time: objects drawn in variable light but drawn in a way to focus the attention of the viewer on the ‘here and now’ and ‘when’ – as the Cubists did? Or, conversely, could these draughtsman-like works slip back into static Classicism? The answer is both yes and no. ‘Yes’, because Buxton does focus our attention on the past and present, yet only to assert that time and change are inevitable and inescapable but not necessarily relentless and joyless. And ‘No’, because against the reality of the ‘here and now’ he ‘shows and tells’ us about particular moments of calm available in our own return rooms - when we will. And yes, there is a form of classicism in these works – in the apparent subject matter and enquiring drawing; competing figments of time are held in balance. Yet consider how writers as various as Keats and Starbuck, Nietzsche and Freud, and Fisher and Lippard, show that the various myths and rituals of the Classical world embody and express the same universal drives. They hold contraries in balance: passionate unreason and rational formulation, past and present. And as such, they remain relevant and open to our constant translation. Buxton is clearly alert to the necessity of such translations. Moreover, he draws upon his own particular predecessors deftly. Maguire suggests Giacometti and Vermeer. Others have suggested CR McIntosh. Irrespective of such alignments, Buxton’s drawings are classical and yet full of a quiet expressionist content, a consciousness of temporality and a recognition of the necessary ‘space’ available in the imaged ‘return room’. In this small, select series there is a certain monumentality without heroic allusion: glazed pots in a room with tall studs, the spatial dynamics of which is marked out for us by verticals and horizontals of timber and folded brown paper, by floorboards and rugs. For some, this is a very ordinary space. For others, it will appear much more than this because of the investment and return made apparent. |